Teigin Incident, the strangest bank heist in Japan

On January 26, 1948, just before closing time, a quiet, middle-aged man entered the Teigin Bank in Tokyo. The man introduced himself as Dr. Jiro Yamaguchi and even carried a business card to prove it.

Later, he would be linked to Sadamichi Hirasawa, a painter, but this connection would remain controversial. His visit, though brief, would shock Japan and create legal debates that would last for decades.

The “Doctor’s” Arrival at Teigin Bank

The man, posing as Dr. Yamaguchi, wore an armband with “Metropolitan Office, City Hall of Tokyo” on it, giving him the appearance of an official. He carried a medical bag and told the bank’s staff he was there to vaccinate them against dysentery, a serious disease that had been a threat in Tokyo after World War II. Trusting him due to his appearance and authority, the staff members had no reason to suspect anything unusual.

But what seemed like a routine health check would soon turn into a deadly encounter.

A Fatal “Vaccine”

Dr. Yamaguchi explained that each staff member needed to take two doses of liquid medicine. Fifteen employees and a child of one of the staff members followed his instructions and swallowed the two doses, believing it was a protective vaccine. Within minutes, all 16 people collapsed. Ten died instantly, and two others passed away in the hospital later. Only four survived.

After administering the poison, Yamaguchi took a small amount of money—160,000 yen, leaving behind an additional 180,000 yen. His actions left a bloody scene and confusion in his wake as he quietly left the bank.

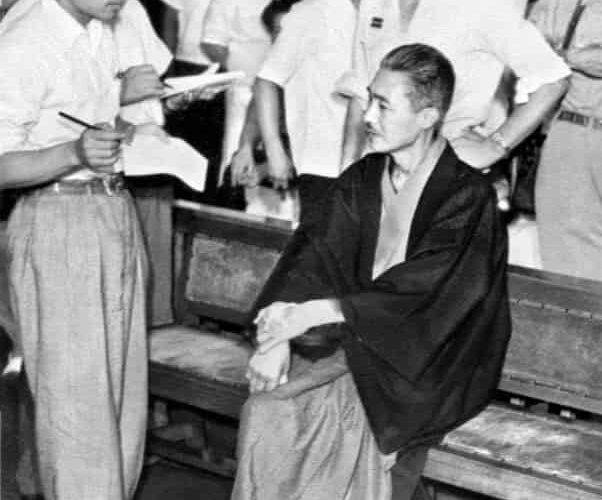

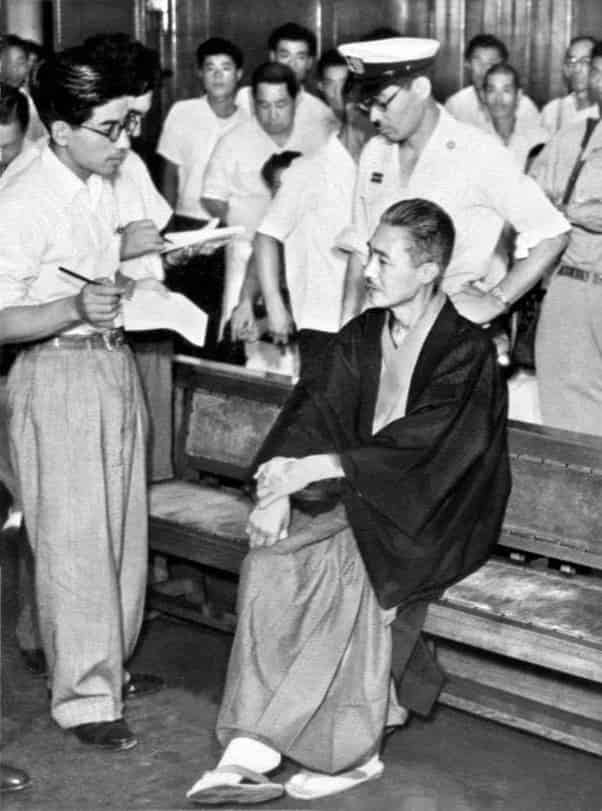

The Investigation and Hirasawa’s Arrest

After months of searching, police finally detained a suspect on August 21. Sadamichi Hirasawa, an artist, came under suspicion. Police discovered that Hirasawa had exchanged business cards with many people, including a man named Shigeru Matsui. Matsui informed the police that he had shared hundreds of cards, one of which belonged to Hirasawa.

Two survivors identified Hirasawa as the person they saw, leading to his arrest. When police searched his home, they found a significant sum of money that he could not explain. Some suspected this money came from selling illegal artworks rather than the bank theft.

During his interrogation, which lasted for three weeks, Hirasawa allegedly confessed but later claimed the confession was forced through torture.

Trial and Conviction

At his trial, Hirasawa’s defense argued that he suffered from a condition called Korsakoff’s Psychosis, a disorder that affects memory and can cause confusion. This illness is linked to alcoholism and was used to explain Hirasawa’s inconsistent statements. Despite this, the court found him guilty, considering his confession as solid evidence, even though Hirasawa quickly retracted it.

In 1955, after years of appeal attempts, his death sentence was confirmed. Hirasawa would spend the next 32 years on death row, as repeated appeals were filed by various legal teams.

Was Hirasawa a Scapegoat?

Doubt remained about Hirasawa’s guilt. There was no direct evidence linking him to the crime. Out of around 40 witnesses, only two identified him positively. His confession, which he said was obtained through torture, raised more questions than it answered. Over the years, many in Japan, including legal experts, suspected he might have been innocent.

In fact, over his three decades on death row, 33 different Ministers of Justice declined to sign his death warrant. This step was required to proceed with an execution in Japan. Even Isaji Tanaka, a strict Justice Minister who signed 23 death warrants in a single day, refused to sign Hirasawa’s.

Some people believe Hirasawa was used as a scapegoat to protect a secret military group within the Japanese Imperial Army, known as Unit 731.

The Mystery of Unit 731

Unit 731, often called the “Asian Auschwitz,” was infamous for its experiments during World War II. This unit focused on developing biological and chemical weapons, often using prisoners as test subjects. Thousands of Chinese citizens and Allied prisoners of war were said to have been used in horrifying medical experiments.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, some members of Unit 731 were reportedly recruited by the Allies, especially the U.S., to work on weapons research in Maryland, instead of facing trial. Supporters of Hirasawa’s innocence believe that a member of Unit 731 may have been the real poisoner at the Teigin Bank.

The method used at Teigin Bank bore striking similarities to Unit 731’s techniques. The victims were given two doses of “medicine,” just as Unit 731 would administer poisons under the guise of vaccinations. The Teigin poisoner’s procedure could resemble a controlled experiment rather than a robbery, as he left more money than he took.

What Poison Was Really Used?

The prosecution argued that potassium cyanide was the poison used in the Teigin Bank murders. However, some symptoms suggested another poison—hydrogen cyanide. Unit 731 had developed a chemical called acetone cyanohydrin, similar in effect to hydrogen cyanide but more powerful. Experts argue that it would be nearly impossible for a civilian like Hirasawa to have obtained this poison. However, someone from Unit 731 would have had access.

Administering poison in the way that the Teigin poisoner did requires experience and skill, something a painter would not likely possess. Hirasawa had no background in chemistry or toxins, which adds to the mystery of whether he could have been responsible for the murders.

Doubts Surrounding Hirasawa’s Guilt

The Japanese legal system’s reluctance to sign Hirasawa’s death warrant points to lingering doubts. During his 32 years on death row, dozens of other convicts were executed, yet Hirasawa was repeatedly spared. Many believed he might not have been guilty, and if he was innocent, executing him would have been a grave mistake.

Some argue that the real reason so many Ministers of Justice refused to sign the warrant was out of doubt rather than tradition, especially given the unusual circumstances surrounding the case.

Even though Hirasawa confessed, he retracted his confession quickly and maintained his innocence for over three decades. He could have admitted guilt at any point, but he never did, which is unusual for someone awaiting execution.

Medical Examinations and Mental Health

Over the years, Hirasawa’s lawyers attempted to appeal his sentence, citing Japan’s Statute of Limitations, which requires execution within 30 years. However, Japanese courts ruled that his death penalty would only begin once a death warrant was signed, and since this never happened, the statute did not apply.

Medical tests showed that Hirasawa’s brain showed signs of a condition similar to encephalomyelitis, indicating possible mental health issues. This condition might support his defense’s partial insanity claim, further complicating the case.

Final Years and Legacy

While on death row, Hirasawa painted and wrote his autobiography, *My Will: The Teikoku Bank Case*. His last years were marked by declining health. In 1981, a new lawyer, Makoto Endo, joined his team and tried to appeal on the grounds that the statute of limitations had passed, but this appeal was denied.

In 1987, Hirasawa died of pneumonia, still officially a condemned man, though his execution was never carried out.

The Enduring Mystery

The Teigin Bank case remains one of Japan’s most infamous criminal mysteries. Was Sadamichi Hirasawa a guilty mass murderer, or was he an innocent man used to cover up the actions of others? The lack of clear evidence, the similarities to Unit 731’s tactics, and the reluctance to sign his death warrant all suggest that the true story may never be fully known.

While Hirasawa’s guilt or innocence may never be proven, his story serves as a reminder of the complexities of justice, especially in cases involving forced confessions and questionable evidence. The Teigin Bank tragedy has left an enduring mark on Japanese history and continues to spark questions about truth, justice, and accountability in criminal cases.

FAQ: Mass Murder at the Teigin Bank

Q1: What happened at the Teigin Bank in Tokyo in 1948?

– In January 1948, a man entered the Teigin Bank posing as a public health official named Dr. Jiro Yamaguchi. He claimed to be there to vaccinate employees against dysentery, a disease that had affected Tokyo after World War II. He instructed the bank staff to drink two doses of liquid, which turned out to be poison. Sixteen people were affected; twelve died, and four survived. The man left after stealing a small amount of money, leaving behind a scene of tragedy.

Q2: Who was Sadamichi Hirasawa, and why was he accused?

– Sadamichi Hirasawa was an artist and painter who was arrested months later as a suspect. He became connected to the case after survivors of the poisoning identified him as the man they saw. Police found a significant amount of unexplained cash at his home, which increased suspicions. Hirasawa confessed to the crime but later claimed he was forced to confess through torture, leading to controversy over his guilt.

Q3: What was the role of Unit 731 in this case?

– Unit 731 was a covert branch of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II that conducted experiments with biological and chemical weapons, often using prisoners as test subjects. Some believe that a former Unit 731 member may have been the real poisoner, as the techniques used in the Teigin Bank massacre resembled methods attributed to Unit 731, such as administering poison under the guise of vaccinations.

Q4: Was the poison used in the Teigin Bank case ever identified?

– During the trial, prosecutors claimed that potassium cyanide was used in the poisoning. However, the symptoms matched more closely with hydrogen cyanide poisoning. Unit 731 had access to a compound called acetone cyanohydrin, which produces effects similar to hydrogen cyanide poisoning, fueling speculation that the poison used may have been linked to the unit’s chemical experiments.

Q5: Why was there doubt about Hirasawa’s guilt?

– There were many reasons for doubt. First, no direct evidence linked Hirasawa to the crime beyond his disputed confession. Out of approximately 40 witnesses at the bank, only two could identify him positively. Additionally, the confession was allegedly obtained through torture, raising questions about its validity. His mental health condition, Korsakoff’s Psychosis, was also brought up as a potential reason he may have been confused or misled during questioning.

Q6: What is Korsakoff’s Psychosis, and how did it affect the case?

– Korsakoff’s Psychosis is a disorder linked to long-term alcoholism, affecting memory and sometimes causing disorientation or dishonesty. Hirasawa’s defense argued that he suffered from this condition, which could explain inconsistencies in his behavior. However, the court did not accept this defense as sufficient to prove his innocence.

Q7: Why was Hirasawa never executed?

– Hirasawa spent 32 years on death row, as 33 different Ministers of Justice refused to sign his death warrant. Under Japanese law, a death warrant must be signed before an execution can proceed. There was widespread belief that Hirasawa might be innocent, and this doubt likely influenced the ministers’ decisions. Even a strict Justice Minister who signed numerous death warrants refused to sign Hirasawa’s, citing uncertainty about his guilt.

Q8: Did Hirasawa ever confess again after his initial confession?

– No, after his initial confession, Hirasawa quickly retracted it and maintained his innocence throughout his time on death row. He claimed that his confession was forced through torture, and he never wavered from his retraction, despite the lengthy time he spent in prison.

Q9: Why do some believe that the Teigin Bank case was a “field test” rather than a robbery?

– The poisoner stole only 160,000 yen but left 180,000 yen behind, which seemed unusual for a robbery. Some speculate that this act may have been a “field test” for chemical or biological agents, consistent with Unit 731’s known experiments, rather than a conventional robbery. This theory suggests the attack might have been an experiment disguised as a crime.

Q10: What impact did the Teigin Bank case have on Japan’s legal system?

– The Teigin Bank case highlighted the issue of forced confessions and led to questions about Japan’s legal procedures. For years, confessions were often accepted without considering how they were obtained, as was the case with Hirasawa’s confession. The prolonged appeals and refusal to sign his death warrant also brought attention to Japan’s capital punishment process and raised concerns over executing potentially innocent people.

Q11: Did the case ever officially close?

– The case remains one of Japan’s most controversial unsolved crimes. Hirasawa was still a condemned man when he died in 1987 from pneumonia, but doubts about his guilt have never been fully resolved. Even today, the Teigin Bank case is a topic of debate, symbolizing issues of justice, forced confessions, and possible misuse of power.

Q12: What is Hirasawa’s legacy?

– Hirasawa’s story has become a symbol of potential injustice in Japan’s criminal justice system. While he was convicted, his case remains debated by legal experts, historians, and the public. His autobiography, *My Will: The Teikoku Bank Case*, captures his perspective on the case and his years on death row, and he is remembered as the longest-serving death row inmate in Japan, raising awareness about legal reforms and prisoners’ rights.