From Slavery to the White House: The Extraordinary Life of Elizabeth Keckly

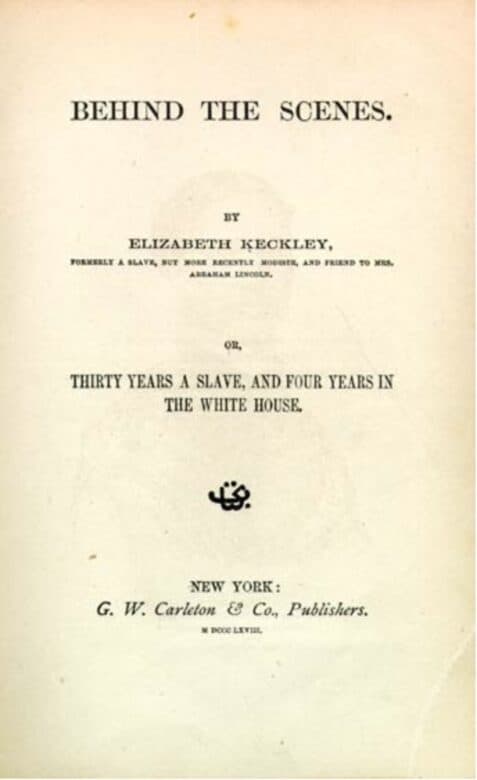

In 1868, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly, also known as Keckley, published her memoir, Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House. This candid work recounted Elizabeth’s incredible journey from slavery to becoming the dressmaker of First Lady Mary Lincoln.

Upon its release, the book stirred controversy, damaging her close relationship with Mrs. Lincoln and tarnishing the reputations of both women. At the time, the American public was unprepared to read the narrative of a free Black woman asserting control over her own life. However, her memoir has since been invaluable for historians reconstructing life in the Lincoln White House and for understanding one of the most intriguing and misunderstood First Ladies in American history. Elizabeth Keckly’s story is essential in comprehending the experiences of both enslaved and free Black women in America.

Born in February 1818 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, Elizabeth’s life began under complex and difficult circumstances. In 1817, while Mary Burwell, wife of plantation owner Colonel Armistead Burwell, was pregnant with their tenth child, an enslaved woman named Agnes (Aggy) Hobbs also became pregnant. Although the exact nature of her relationship with Colonel Burwell is unclear, it is likely that Aggy’s pregnancy resulted from sexual violence or a non-consensual encounter. Despite being the daughter of the plantation owner, Elizabeth was born into slavery.

Aggy was married to George Pleasant Hobbs, an enslaved man who worked on a nearby plantation, and although Elizabeth was not his biological child, George treated her as his own, and she considered him her father. Her mother gave her George’s family name in a gesture of resistance, an early sign of her family’s strength and autonomy. The truth of Elizabeth’s parentage was unknown to her until she was older. Her birth was noted in the Burwell family records as “Lizzy—child of Aggy/Feby 1818.”

Elizabeth spent her early childhood among other enslaved children, helping her mother, who was a domestic servant valued by the Burwells. Aggy was beloved by the family and, unusually, was allowed to read and write—a skill she passed down to her daughter. She also taught Elizabeth to sew, a talent that would later shape her future. One of Elizabeth’s first tasks as a five-year-old was to care for Burwell’s infant daughter, also named Elizabeth, a child she grew very fond of, calling her “my earliest and fondest pet.” Despite her affection, one incident involving the baby earned Elizabeth her first brutal punishment, a memory she would carry throughout her life:

[My old mistress encouraged me in rocking the cradle, by telling me that if I would watch over the baby well, keep the flies out of its face, and not let it cry, I should be its little maid…I began to rock the cradle most industriously, when lo! out pitched little pet on the floor. I instantly cried out, ‘Oh! the baby is on the floor;’ and…I seized the fire-shovel in my perplexity, and was trying to shovel up my tender charge, when my mistress called to me to let the child alone, and then ordered that I be taken out and lashed for my carelessness. The blows were not administered with a light hand…This was the first time I was punished in this cruel way, but not the last.]

As Elizabeth matured, she became increasingly aware of the harsh realities of slavery. Besides enduring physical punishment, she witnessed her mother’s grief when George Hobbs was forcibly separated from their family. Colonel Burwell, in what he called a “reward” for Aggy, arranged for George to live with them for a short time. Elizabeth vividly remembered the joy this brought her mother, but their happiness was brief. One day, Burwell presented George with a letter commanding him to join his enslaver in the West, giving him just two hours to say goodbye to his family. The painful separation left a deep mark on Elizabeth, as described in her memoir:

[The announcement fell upon the little circle in that rude-log cabin like a thunderbolt…how my father cried out against the cruel separation; his last kiss; his wild straining of my mother to his bosom…the fearful anguish of broken hearts. The last kiss, the last good-bye; and he, my father, was gone, gone forever.]

Such separations were common, and most enslaved families faced the constant threat of being torn apart. Elizabeth and her mother never saw George Hobbs again, though he continued to write letters to them, an extraordinary circumstance considering that most enslaved people were barred from literacy. In one letter, George wrote:

[Dear Wife: My dear beloved wife I am more than glad to meet with opportunity writee thes few lines to you by my Mistress…I hope with gods helpe that I may be abble to rejoys with you on the earth and In heaven lets meet when will I am detemnid to nuver stope praying, not in this earth and I hope to praise god In glory there weel meet to part no more forever…]

When Elizabeth was fourteen, she was sent to work for Burwell’s son, Robert, a Presbyterian minister in North Carolina. Her time there was marked by cruelty. She suffered regular beatings and endured years of sexual abuse by a local store owner, Alexander McKenzie Kirkland, which resulted in the birth of her only son, George. Reflecting on her son’s birth, Elizabeth expressed the deep pain of this experience: “If my poor boy ever suffered any humiliating pangs on account of birth, he could not blame his mother, for God knows that she did not wish to give him life; he must blame the edicts of that society which deemed it no crime to undermine the virtue of girls in my then position.”

In 1842, after years of hardship, Elizabeth returned to Virginia, where her master’s financial difficulties led to her relocation to St. Louis, Missouri, with the Garland family. It was here that Elizabeth’s skill as a seamstress flourished. Refusing to allow her aging mother to be hired out as labor, Elizabeth used her sewing talents to support the family. She began taking orders from St. Louis’ wealthy white women and quickly built a thriving business. Over time, her success brought her into contact with influential figures, including Mary Lincoln, wife of future President Abraham Lincoln.

In 1850, Elizabeth married James Keckly, a free Black man, after securing an agreement from her master to purchase her and her son’s freedom. Raising the $1,200 necessary to buy their emancipation was a challenging and slow process. Eventually, through the generosity of her clients, Elizabeth succeeded in paying for her and her son’s freedom, and in 1855, she received her emancipation papers.

Following her emancipation, Elizabeth moved to Washington, D.C., where she continued her sewing business. Her skill and reputation grew, and she eventually became the dressmaker for Mary Lincoln, a role that gave her a unique perspective on the Lincoln family and life in the White House during the Civil War. Elizabeth’s memoir offers detailed and personal insights into the Lincoln household, the First Lady’s grief after the death of her son Willie, and the everyday challenges faced by a family leading the country through its darkest times.

In 1868, Elizabeth published her memoir, hoping to clear her name and that of Mary Lincoln, who was mired in financial and personal difficulties. Unfortunately, the publication of her book led to public outrage. The intimate details of her relationships with the Lincolns, as well as her candid revelations about the First Lady’s private life, were considered breaches of trust. Although her intentions were to humanize Mary Lincoln and reveal the inner workings of the White House, Elizabeth’s memoir was met with harsh criticism.

Despite the controversy, Elizabeth Keckly’s story remains a testament to resilience, courage, and the pursuit of freedom. Her journey from slavery to the White House, and her role in shaping history, continues to inspire and provide valuable insights into the lives of both enslaved and free Black women in America.

FAQ: The Life and Legacy of Elizabeth Keckly

1. Who was Elizabeth Keckly?

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly (1818–1907) was a formerly enslaved woman who became a successful seamstress, civil rights activist, and author. She is most well-known for her role as the personal dressmaker and confidante to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln during and after the American Civil War.

2. What is Elizabeth Keckly famous for?

Elizabeth Keckly is best known for her book Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, published in 1868. The memoir detailed her life from slavery to her time working closely with the Lincolns, providing an insider’s look at the Lincoln White House.

3. How did Elizabeth Keckly gain her freedom?

Elizabeth Keckly purchased her freedom in 1855 after years of hard work as a dressmaker in St. Louis. She raised $1,200 with the help of her patrons, which allowed her and her son, George, to be emancipated from slavery.

4. What was Elizabeth Keckly’s relationship with Mary Todd Lincoln?

Keckly and Mary Todd Lincoln developed a close professional and personal relationship. Elizabeth became Mary’s personal dressmaker and confidante, assisting her through personal tragedies such as the death of President Abraham Lincoln and their son Willie. Their relationship, however, was strained after the publication of Keckly’s memoir.

5. Why was Behind the Scenes controversial?

The memoir Behind the Scenes was controversial because it provided an intimate look into the private lives of the Lincoln family. Elizabeth’s candid revelations about her relationship with Mrs. Lincoln, as well as the inclusion of private letters, led to public criticism, particularly for violating the strict norms of privacy expected at the time.

6. How did Elizabeth Keckly’s memoir impact her life?

The publication of Behind the Scenes damaged Keckly’s relationship with Mary Todd Lincoln and led to public backlash. Many criticized her for disclosing private details of life in the White House, which hurt both her reputation and career.

7. How did Elizabeth Keckly contribute to the African American community?

In addition to her successful dressmaking business, Keckly co-founded the Contraband Relief Association in 1862. The organization provided aid to formerly enslaved individuals (called “contrabands”) who had fled to Washington, D.C., during the Civil War.

8. How did Elizabeth Keckly become involved with the Lincoln family?

Elizabeth Keckly’s reputation as a skilled dressmaker reached Mary Todd Lincoln through mutual clients. After being recommended, she was hired to create dresses for Mrs. Lincoln, leading to a long-term professional relationship and personal friendship.

9. What happened to Elizabeth Keckly after the Lincolns left the White House?

After the Lincolns left the White House, Keckly continued her work as a seamstress but faced challenges due to the controversy surrounding her memoir. She also remained active in charity work, especially with the African American community. In her later years, she taught at Wilberforce University and lived in obscurity until her death in 1907.

10. What is Elizabeth Keckly’s legacy today?

Keckly’s legacy is that of a pioneering Black woman who overcame the horrors of slavery to become a successful entrepreneur, confidante to one of America’s most famous first ladies, and author. Her memoir is considered an important historical document, offering a unique perspective on both the Civil War era and Mary Todd Lincoln.